“A funny thing happened on the way to the Forum.” Diyarbakir doesn’t really feature on the itinerary for most tourists but if you want see a Roman Forum pretty much intact, bustling and open for business, go to Diyarbakir. They’ve got one. You’ll get swept away by a time machine.

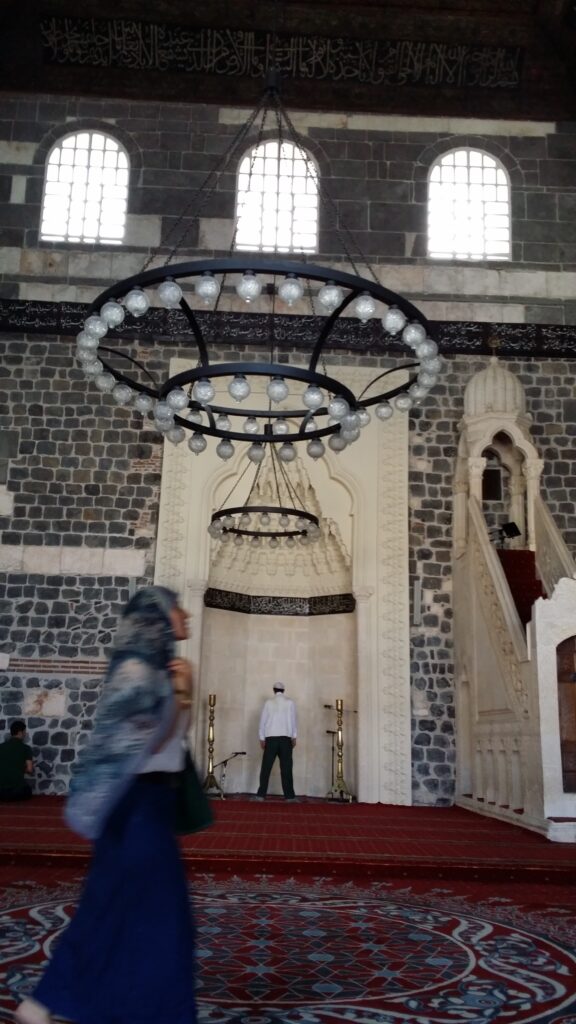

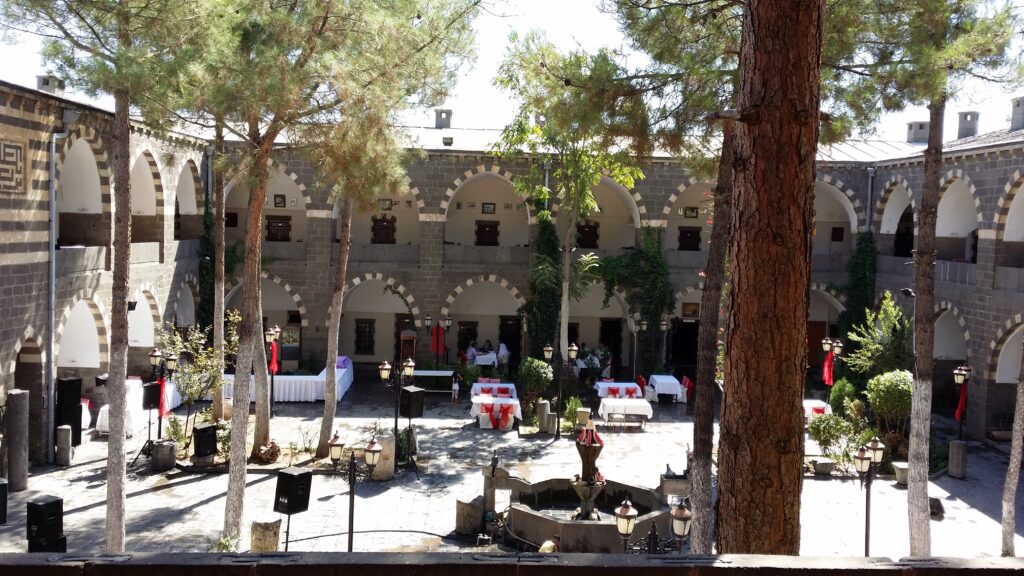

The Ulu Cami is the Great Mosque of Diyarbakir. The mosque complex is made up of various places of worship and study with buildings constructed around a central courtyard that replicates the old Roman Forum and Basilica in terms of its ground plan and its location.

Eastern Turkey Travel – 12 Day Tour of Eastern Turkey (easternturkeytour.org)

While the current building is dated primarily from between the eleventh and sixteenth centuries it uses a lot of materials and design features from the old Roman forum. The only difference is the ablution fountain in the centre of the courtyard. The mosque follows the footprint of the old Basilica and Church built by Emperor Heraclius (610 to 641 AD) and which was dedicated to St. Thomas.

Article continued below…

Interestingly, the Ulu Cami copies the design of the Great Mosque in Damascus, itself a nod to a Classical past, and although being built on the footprint of a Christian Church still lines up perfectly with Mecca, a requirement for prayer in Islam. Most churches converted to mosques don’t do this: they are internally skewed to make sure the faithful face Mecca at prayer. How much depends on location. Aya Sofia in Istanbul is only slightly off while the Selimiye Mosque in Nicosia, Cyprus, converted from a Catholic Crusader Cathedral, is significantly off.

Aya Sofia in Istanbul and the Selimiye Mosque in Nicosia, Cyprus

You can see the adjustment by looking at the orientation of the Mihrab – the marker for the direction of Mecca. The Ulu Cami of Diyarbakir, through an accident of geography, sits on the same longitude as Mecca and consequently, lines up perfectly.

What we see in this unique part of Diyarbakir is a true synthesis in design: Rome reimagined by the Seljuk Turks and Artukids.

It is thought that the eastern portico is a straightforward reconstruction of a previous Roman building, not just that its columns and reliefs come from Roman monuments but that this part of the building could have been the internal back wall, or “scene” of a theatre with the columns and entablatures later reconstructed as a portico, and the main entrance to the complex. It is also interesting that the courtyard is on the original floor level of the old Forum as one needs to step down a flight of stairs from the main central street to enter. One has to do the same to enter the Hasan Paşa Hanı across the main street…. more of that shortly.

The decoration of the entablature is based on two bands; the oldest one is placed at the top; a frieze with a vine stalk forming loops around leaves and bunches of grapes and which probably belongs to a 6th century Byzantine building while on the lower band there is a Kufic inscription from the Artukid period which says that the portico was completed in 1117.

Most of the northern side of the courtyard is occupied by a third portico built on columns with Corinthian capitals also recycled from the original Roman building; this portico leads to Mesudiye Medresesi, an Islamic school.

The capitals are different in size and decoration, so clearly, they come from various ancient buildings; it is possible that they were gathered and used for the mosque which preceded the 11th century Ulu Cami which itself used recycled architectural elements. A Persian poet and traveller who visited Diyarbakir in 1046, reported that the interior of the mosque was supported by hundreds of ancient columns.

The Mesudiye Medresesi, adjacent to the Ulu Cami and one of the first Theological Schools in the region, was completed by the Artukids in 1198. Its decoration is based on the contrast between the prevailing black basalt stones which come from the Karacadag mountain and a white decoration. According to the inscriptions present along the wall more than theology was taught here; canon law, medicine, physics, mathematics, biology, chemistry, literature and philosophy were all taught at this religious school, indicative of the broad range of academic enquiry typical of Islam at this time.

The mosque is associated with a local lore concerning co-use of the site with Christians for a period of time shortly after the Muslim conquest of the region in 639 and while this may, or may not, be true, it is certain that Christian communities continued to have a vibrant life in the city attested to by the very important churches that still exist here. There are a number of religious traditions that feed the culture, both human and architectural, in Diyarbakir.

The Ulu Cami is a great place to rest and relax in the cool – when it isn’t prayer time – and many locals do just that. Expect to step around the occasional sleeping local!

Ulu Cami with shoes off, ready for a catch up

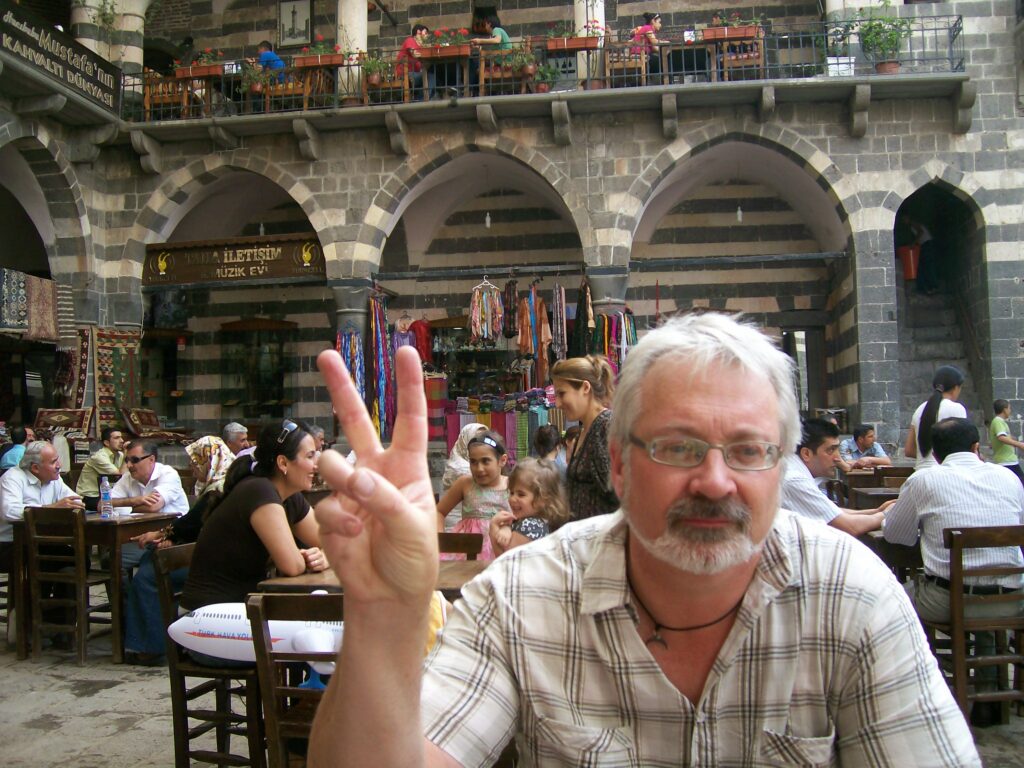

If you want to relax in an atmosphere with a bit more buzz going on, step outside the precinct and cross the road to enjoy the bustle of Hasan Paşa Hanı, built between 1575-76 by Hasan Paşa, as an important city facility for merchants and travellers on the Silk Road. Caravanserais are dotted around the centre of the city and hark back to the days when this was a major junction on the Silk Road and an important market in its own right. This is one of the biggest but only one of three in about a 300-metre stretch. You step down off the busy main street into a vibrant and colourful atmosphere kept cool by canvas awnings stretched over the courtyard and by fine mists of water sprayed in the air that produce a sweet, fresh space to sit, sip your coffee and watch the goings on. Alternatively, there’s breakfast which in the Hasan Paşa Hanı is always outstanding.

Hasan Paşa Hanı

For a variation on the Han experience, just around the corner, down the street and a bit passed several busy blacksmithing establishments, is the Sülüklü Hanı. It has become a popular meeting area for young and old has been one of the most remarkable inns in the city due to its specific origins.

Sülük is the Turkish word for “leech.” The Han takes its name from the leeches that were pulled from the well by doctors and healers for medical treatments back in the 1700’s when this inn was built.

It is a peaceful environment for everyone who wants to drink pistachio coffee unique to Diyarbakir and this region of southeast Turkey in an authentic environment but now, however, devoid of leeches. In fact, if you want leeches, you’ll have to go all the way to Bridgend in South Wales where Europe’s biggest medical leech farm is thriving; it’s a long way to go for a leech and but you won’t get a coffee there.

Two pistachio coffees please and thank you

Just a little way down the main road to the Mardin Gate and adjacent to this stretch of the Wall is the Deliller Hanı, literally the Inn of the crazy or mad people although we’re not talking medically mad here.

The “Crazy” people being referenced are members of a light cavalry unit within the Ottoman Empire. They were named for their daring and reckless bravery. Their main role was to act as shock troops but also as personal guards for high-level Ottoman officials in the Rumeli (Balkans) during peacetime. The first “Deli” detachments were created by the Bosnian Governors in the Balkan Provinces.

The leader most associated with these troops was Gazi Husrev Beg, who employed about 10,000 of them. Gazi Husrev Beg was an example of the interconnected ethnic mix that typified the efficiency and meritocratic nature of Ottoman administration at this time. He, himself, was a Slav from Bosnia and among his many accomplishments was the development and improvement of the urban environment in Sarajevo, Bosnia. Due to the effectiveness of Gazi Husrev Beg and his Deli troops, Governors in other border zones and difficult to control areas adopted the system.

Gazi Husrev Beg

From its innovation in Rumelia (Balkans) in the mid-15th century as a border protection unit and as targeted shock troops, the Corps’ concept had been widely adopted by the 16th century. Bıyıklı Mehmed, the man who took Diyarbakir for the Ottomans and who became its first Ottoman Governor, was a man in the same mould as Gazi Husrev Beg. These “Deli” units played a prominent role in the border wars between the Ottomans and Persians and to maintain the peace in the post Amasya Treaty settlement (1555).

Their Han, appropriately positioned near the main Gate on the road South for speedy deployment to potential trouble spots, is now a hotel. Interestingly, most of Diyarbakir’s cultural attractions seem to be behind unassuming facades accessed through ancient doors and gates. This is also true of the city’s Christian churches.

Article continued below…

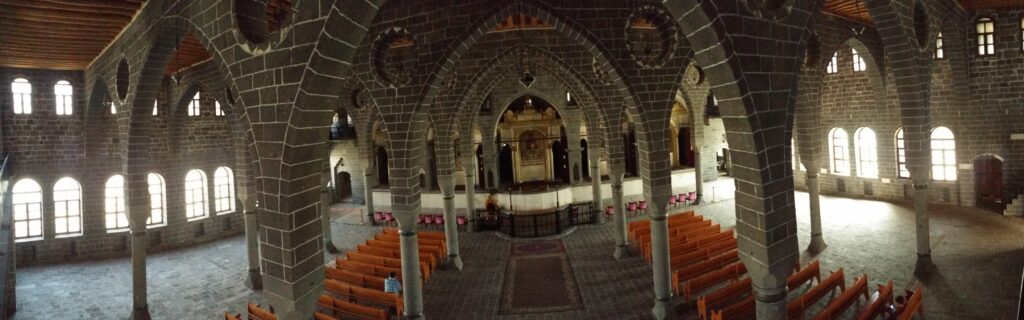

Church of St. Giragos, or Surp Giragos, is an historic Armenian Apostolic Church and is the largest Armenian church in the Middle East. However, it is accessed down a few narrow alleys and through an anonymous door; the church is to be found in a handsome precinct but inside a fairly unremarkable building there is a flamboyant expression of High Church design.

Church of St. Giragos

The original church on this site dates from the early 15th century and was expanded over the course of the 17th and 18th centuries, before it was destroyed by a devastating fire in 1880. What you see now is the rebuilt version that expresses the size and confidence of the Armenian community in Diyarbakir at this time, with its bell tower being the tallest structure in the city when it was completed. Abandoned during WW I following the expulsion of the Armenian community, the building went through a number of uses before falling into a state of disrepair. The building was fully renovated between 2009 and 2011 but was closed for a period shortly after as the State took over ownership. The Church reopened for visitors and worship in 2022. This Church should be on everyone’s itinerary as a point of contemplation about the effects of conflict and the importance of reconciliation.

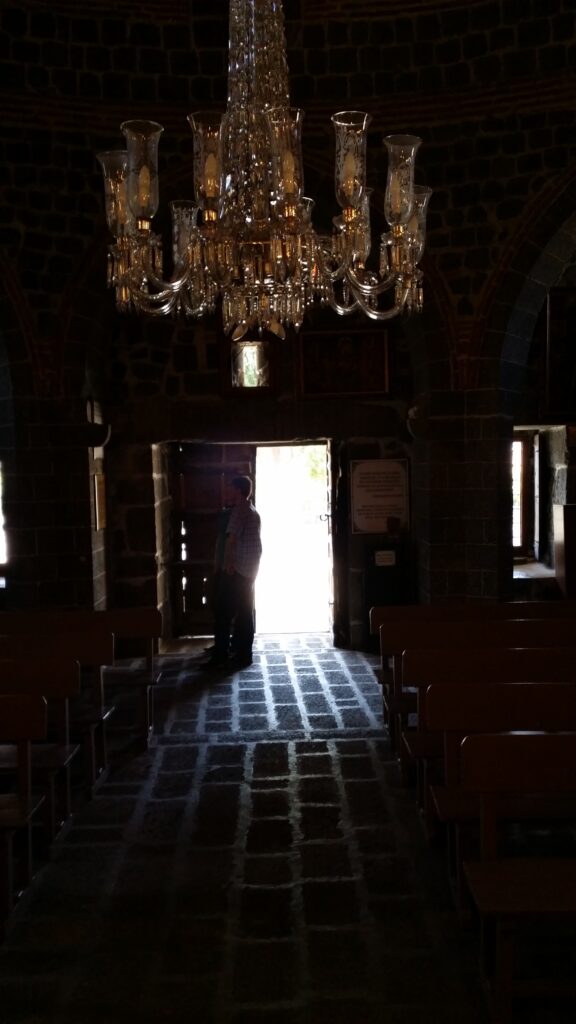

The other “must see” church in Diyarbakir is the Church of St. Mary also known as Meryamana Kilesi. This is a Syriac Orthodox Church under the jurisdiction of the Syriac Archdiocese of Mardin, headed by the Syriac Metropolitan based there. This particular church is a monument to durability.

Meryamana Kilesi

First constructed as a pagan temple in the 1st century BC, the current construction dates back to the 3rd century. It even survived the devastating Mongol invasion and occupation of this part of Anatolia. The church has been restored many times, and is still in use as a place of worship today. While it is modest in size, it is an island of tranquillity in the hustle and bustle of the outside world. Here you can still here Aramaic, the language spoken by Christ; it is a thread that leads back 2000 years to the start of the modern era.

The fascinating history of Diyarbakir is enveloped by its most obvious and significant feature; its magnificent City Wall. After the Great Wall of China, these defensive walls comprise the longest wall in the world. Dating from the late Roman period, they were constructed between 297 AD, when the main fortress was built, to 349 AD with the Emperor Constantius II being the main driving force. Constructed from the black/grey basalt that remains from the Karacadağ volcano and which are scattered across the region they are an imposing feature imprinted onto the landscape.

The walls feature four Main Gates: Dağ (Mountain) Gate, Urfa Gate, Mardin Gate, and Yeni (New) Gate. Additionally, there Are 82 Watch Towers and the walls’ average height is over 10 metres while they vary between 3 and 5 metres in thickness. They stretch to 6 kilometres in length and their basic construction material, basalt, is very hard and durable. However, they could not resist the power of the Ottomans who were among the earliest innovators of the strategic and tactical use of artillery.

The Ottomans took Diyarbakir in 1514 in the campaigns of Bıyıklı Mehmed who then became the first Ottoman Governor. This followed the decisive victory of Sultan Selim I, otherwise known as Selim the Grim, at the Battle of Çaldıran on August the 23rd 1514. While 1514 demonstrated the use of mobile artillery by a field army for siege warfare at Diyarbakir, Çaldıran was the first tactical use of mobile artillery and musketry in a battlefield context in history. Fought on what is now the border between Iran and Turkey it was a stunning Ottoman victory and it, and the Treaty of Amasya, set the border between the Ottomans and Persians until modern times and this border still remains between Iraq and Iran. The reality of Ottoman rule on the ground was confirmed by the 1555 Peace of Amasya which concluded the Ottoman–Safavid War of 1532–1555. Events sometimes have a very long reach. The consequences are with us still, imprinted on the ground in modern borders.

It’s hard to know where to stop but before I do, I can’t not mention food and one of the great specialities of Diyarbakir and the southeast region of Turkey: liver kebabs! I know what a lot of you are thinking, but it’s time to think again. The liver kebabs of Diyarbakir are amazing.

Once referred to as a poor man’s dish it has been “discovered” as a nutritious, healthy dish bursting with delicate flavour and is now to be found among the delicacies featuring on many menus in swanky metropolitan restaurants, but here you’ll get the genuine article, cooked in front of you and served with panache and pride. Don’t miss it. Chefs fire up the grills before dawn and they’re going until midnight. The locals eat it for breakfast, lunch or dinner, so there’s really no excuse.

Culturally, politically, religiously, geographically, gastronomically and historically, Diyarbakir remains a pivotal city in this important region and one which most people miss, which is why you really should make it a destination on your next trip to Turkey.

It has been a real pleasure writing this travel journal for you, we are laughing at the moment because we are dreaming about mouth watering liver kebabs from Diyarbakir.

Just liver the dream lol.

Best wishes to you all Sally and Nick.