Whoever thought that Ale – or “liquid bread” – would come about because of something called Wandering Wheat? But it is true! Wild wheat (or grasses) still grow in southeast Anatolia. Although supplanted by large scale farming and commercial wheat varieties, they still occur, much as they did in Neolithic pre-farming times, although not in quite such profusion.

The locals call these varieties “wandering wheat” because they would appear, in patches in different places, often kilometres apart, depending on the wind, soil and rainfall each Spring. Until fairly recently locals preferred these ancient varieties before higher yielding commercial varieties were introduced.

Now locals only tend to farm these ancient varieties for their own consumption and if conditions permit. It’s a trade off; while yields are much higher now, the nutritional content in these ancient wheat and grain varieties is higher. There is also the taste. These varieties “wander” like nomads and pop up by chance because they are ancient survivors seeded on the wind in a world of mechanised farming. In the Neolithic, they proliferated. This whole area was a mix of savannah woodland dotted with areas of grassland. A number of important foods derived from this Anatolian larder apart from wheat.

Nutritious staples like rye, barley, lentils and pistachio, and much else besides, thrived here and still form the basis of the local diet. In the Neolithic this was a land of plenty. This is where bread – and possibly beer – originates.

In the Mesopotamian myth “How grain came to Sumer” the brothers Ninazu and Ninmada, the servants of An, gift grain and flax to mankind. The story says:

“Men used to eat grass with their mouths like sheep. In those times, they did not know grain, barley or flax. An brought these down from the interior of heaven. An piled up the barley, gave it to the mountain. He piled up the bounty of the Land, gave the innuha barley to the mountain……… Let us go to the mountain, to the mountain where barley and flax grow; …… the rolling river, where the water wells up from the earth. Let us fetch the barley down from its mountain……………. Let us make barley known in Sumer, which knows no barley.”

Article continued below…

To the people in the lower parts of Mesopotamia these Anatolian uplands were the “mountains” they were talking about; this elevated plain and the eastern Anatolian highlands and mountains which are the source for both the Tigris and Euphrates.

Ancient peoples always attributed their greatest skills and their most valued treasures, such as gold, silver, agriculture and writing to the intervention of their Gods and it makes for a rich and vibrant story, but there is another story no less rich and no less fascinating.

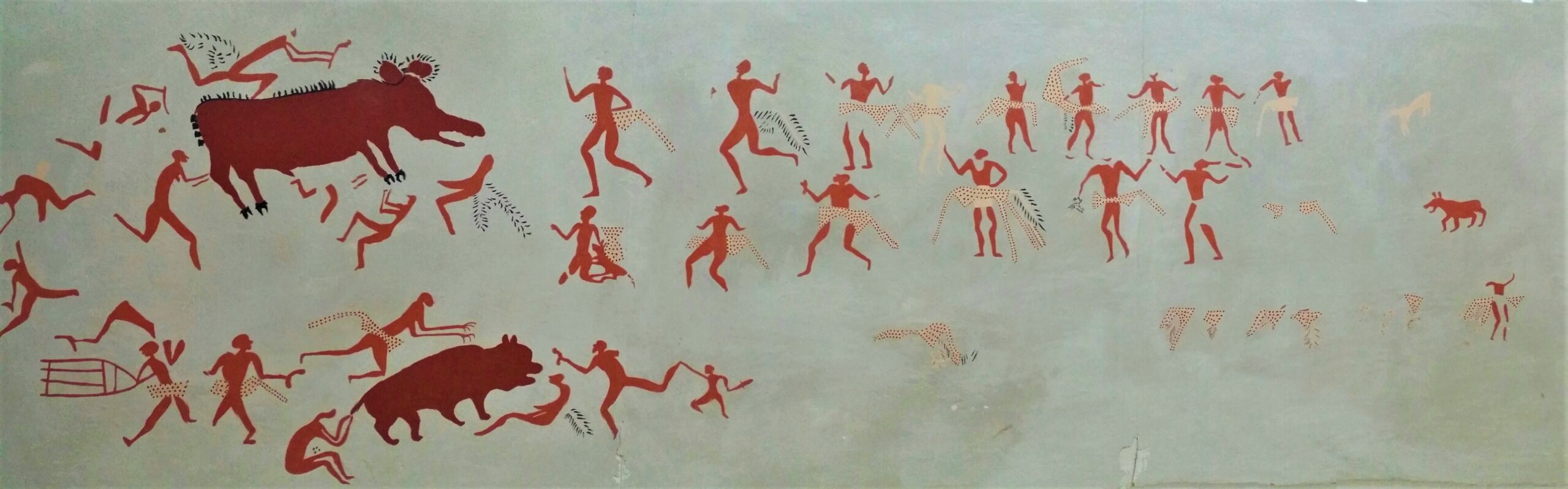

Imagine, if you will, the scene back in 12,000 BC or so. Stretching before you is a large undulating plain covered by trees interspersed with areas of open grassland. It is mid or late summer; the grass is tall and yellow and rippling like gentle waves in a barely perceptible breeze. Here and there small groups of people, including small children, are slowly moving through the grass chattering and laughing as they work. No idle hands here!

The little ones are, as best they can, stripping the seeds of grain from the stalks by hand, the grown-ups are using sickles made from bone or wood and sharp flint microliths, and women are carrying infants on their backs.

Article continued below…

Everybody carries bags made from skins or flax to carry the grains back to their camp, a short distance away through some trees on the bank of a small river. On the other side of the river is a wetland area where reeds, wildfowl and fish are to be found in plenty. Wisps of smoke rise above the tree tops identifying the location of the camp, until the breeze carries them away. Everything they need is here and this is a place they have been frequenting for generations. They will move on but many of their tools for processing the grain and making tools for life will remain for use next year. Granny’s grinding stone weighs 40 kilos or more and just isn’t very portable. It’ll be the focus for a home when people return next season.

They are also starting to store produce like wheat, barley and lentils for later use. Gradually, their stays become longer and over generations this site will become a permanent village slowly expanding and modifying the local environment as time and generations pass. Each season as the people harvest grains, nuts and fruits the seeds imperceptibly change in an evolution driven by these early hunter gatherers and to which they are totally oblivious. Gradually cottage industries will establish themselves and plaster walls and terrazzo floors will appear; the very first industrial activity undertaken by humans. Cultures will settle down and flourish around places where ancestors are buried and slowly, over hundreds of generations, the modern world is being born.

Far fetched? Well, no. Back in the 1960’s an American agronomist called Jack Harlan, harvested wild wheat in south-eastern Turkey as gatherers would have done 12,000 years or more ago. At first, he tried hand-stripping the mature wheat ears, then he tried using a replica of an ancient sickle, a row of razor-sharp flint blades embedded in a wooden handle. Although lacking the expertise of the ancient men and women who lived in the same spot in the foothills of Karacadağ thousands of years ago, he quickly grasped the essentials.

Jack Harlan was a specialist on the domestication of crops. His Anatolian harvest experiment was one of the earliest examples of experimental archaeology in Turkey. Although hand stripping was less effective than the sickle, both methods proved to be quite effective. A crop of 2.05-2.45 kilograms per hour could easily be harvested. That amount reaped about 46 percent of actual grain, so it was easy to have a yield of one kilogram of grain per hour. At this rate, a family – say eight people – would be able to harvest a year’s supply easily within three weeks during the harvest season. The fact that these wild grains still exist and still proliferate links present to past and the fact that they appear in areas usually not far from ancient Neolithic sites is remarkable. In the province of Diyarbakir, occasional batches of wild wheat still grow on the outskirts of the Karacadağ Mountains from where einkorn, the first domesticated wheat, originates.

Limestone platters in Urfa Museum. Left hand platter 2.5 feet diameter, right hand platter 2.0 foot diameter (approximate)

Large stone vessels and platters like these above are all found insitu where they were used. They are clearly intended for large scale food production and serving and equally clearly they are not portable. Could it be that these domestic items acted like the grain of sand in an oyster that produced the “pearl” of settled living?

But what of storage? That’s the next problem if you are producing surpluses. Not far south of here, just in northern Syria is Jerf el Ahmar, a place very like our imaginary village in its later stage and where food storage is clearly being practiced. Jerf el Ahmar is part of a cluster of sites that straddle the current Turkish/Syrian border. It is an early Pre-Pottery Neolithic settlement on the Euphrates.

There was, in the centre of the settlement, a series of circular, subterranean buildings that were monumental in scale, up to 9m in diameter and 3m deep and which were partitioned and used for storage. Evident at the site was wheat, barley and lentils but all of pre domesticated varieties. The other part of this story of course, is beer.

Humans have been brewing beer or wine for millennia. When they weren’t imbibing, they were getting stoned on natural plant intoxicants like marijuana. In fact, there has been an ongoing debate as to whether beer – and not bread – was the first product made from pre domesticated crops. Some have suggested that the discovery of fermentation could have been the spark that triggered the targeted selection, and ultimately domestication, of certain crops. Let’s face it, fermentation is probably the most astonishingly useful chemical reaction we ever happened upon.

Article continued below…

From bread, to preservation of foods, making yogurt and cheese and from alcohol to modern pharmaceuticals it’s simply too useful to be true. But here we are, in the Neolithic with humans getting smashed when they could. It’s a natural product in over ripened fruits. The thing is, we should not really be liking it this much. Most of us prefer fresh fruit rather than fruit that’s gone off and all plant drugs are, including nicotine, caffeine, cannabis and cocaine, bitter for a reason. The astringent taste warns herbivores to back off. But not us. It seems that humans are animals built to get hammered. More than that, fermented grain, which sees its starch transformed into sugars, hangovers notwithstanding, is well known for its beneficial properties, including an increase in nutritional and calorific value, also making it easier to digest. Alcohol is communal but it’s not just about the buzz, the social lubrication or the opportunities for chance, casual sex. In short, humans have been using intoxicants not just for the mellow contribution to social or communal events, but for ecstatic and transcendental spiritual experiences for a very, very long time. It really is “From Ale to Eternity.”

The fact is that early grain crops would have been far better suited to the production of a mildly alcoholic gruel or beer than actual bread. Preliminary results from chemical studies made on two stone vessels from the PPN necropolis at Körtik Tepe, near Diyarbakir, have yielded traces of tartaric acid that accrues during the wine production process. Recently, further chemical analyses on six large limestone vessels from Göbekli Tepe with capacities of up to 160 litres, were found in-situ in Level II contexts at the site. During excavations, it was noted that some of these vessels carried grey-black adhesions. Early analyses made on these substances returned partly positive indicators for calcium oxalate, which develops in the course of the soaking, mashing and fermenting of grain. Together with the astonishing variety and profusion of wild animal bones found at Göbekli Tepe, what we seem to have here is serious feasting.

It is interesting to note, however, that while evidence for some habitation is emerging at Göbekli Tepe’s Level II layer in terms of food preparation in the form of these large vats, stone bowls and grinding stones, there is no evidence for any storage of grains as at Jerf el Ahmar. Göbekli Tepe seems to have an event driven imperative rather than a domestic or mixed purpose which we see at other sites from the same period.

Fermentation also negates Ergotism, a form of poisoning resulting from eating grains, especially rye and wheat, infected with Ergot, a fungal spore occurring in damp grains. It produces violent hallucinations and can kill. Hallucinations tend to be a more privileged high, something for initiations or reserved for important people, not such a bad thing at the right time, but the problem is that it is unpredictable and this kind of spiritual ecstasy must have both context and control; much better to get smashed on beer which you made and understand and can be enjoyed by all, not just the Shaman. Since hallucinogens are much more intense and more likely to be used for initiations or by initiates for specialized events such as divination, healing or communing with ancestors or with animal guides, it tends to be reserved. Beer is much more of a communal thing. More democratic.

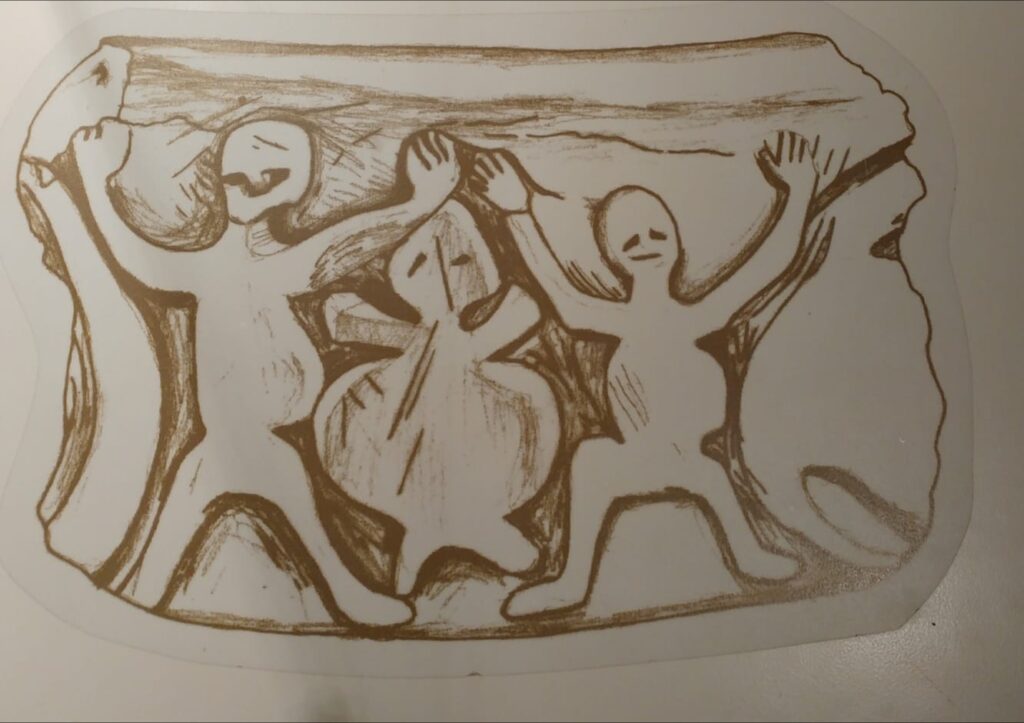

Of course, summing it all up is the evocative limestone bowl fragment from Nevali Çori that preserves the image of two human dancers next to a large turtle, a known animal of spiritual power, also in the position of dance. It’s a Neolithic rave. In many traditional societies, it was the women who did the brewing. I’d like to think it was like that at Göbekli Tepe. It was certainly the case in ancient Sumer; many centuries later, a Sumerian hymn to the Beer Goddess, Ninkasi (yes, they had one) starts:

“Let the heart of the fermenting vat be our heart. What makes your heart feel wonderful, makes also our heart feel wonderful………You poured a libation over the brick of destiny……Drinking Beer in a blissful mood.”

Cheers. Who is bringing the bread and cheese?

And don’t forget the Brick of Destiny.

Follow us on Facebook and Instagram for news, journals, exciting tours and more. Best Wishes Sally and Nick