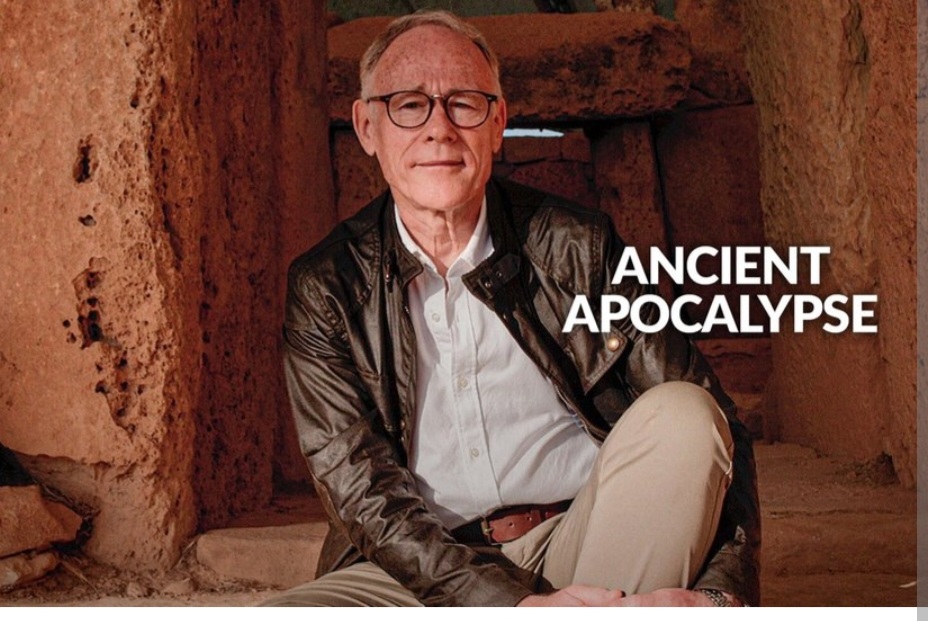

As featured in Graham Hancock’s 2022 Netflix Series.

A new series offers a different theory behind the creation of the ancient underground cities of Cappadocia. Ancient Apocalypse delves into sites across the globe that hint at a forgotten episode in our human story. Several of the most important sites covered are in Turkey. We visit all these Turkish sites, but Derinkuyu is one of the most intriguing, mostly because it has virtually no context or artefacts which we can use to frame it in time.

There can be no doubt about it……extraordinary underground cities, especially ones as extensive as the ones found in Cappadocia, are exciting, mysterious and often challenging. They can be challenging to interpret, they can be challenging to understand and often, they are challenging to explore and visit. Dark, confined, claustrophobic, they nonetheless draw us in and provoke our curiosity and wonder; they invite speculation. But you’ll be pleased to know that there are now electric lights to show you the way! Every time we visit, that mix of reactions and emotions never diminishes.

Nobody knows for sure, but there are about 200 underground cities, settlements and cave complexes in Cappadocia. In fact, there’s almost as much underground as there is above ground and more are being discovered every year as houses are extended and as developers expand modern towns.

A little bit of extra reading…

The most recent discovery is what may be the largest cave complex yet, at Nevşehir, although it could be years before this is open for the general public. The sheer scope and complexity of the archaeology in Cappadocia invites a very broad range of speculation from the fantastic to the mundane. However, the difficulty with assessing these underground complexes is that so many of them have simply been swept clean, but here is what we know:

Some of the earliest work is attributed to the Hittites and then the Phrygians in the mid Bronze Age and then the Iron Age, sometime after 2000 BC, although some of the shallower sections could be older. In Derinkuyu, the largest complex open to visitors, a few Hittite artefacts were discovered in upper levels.

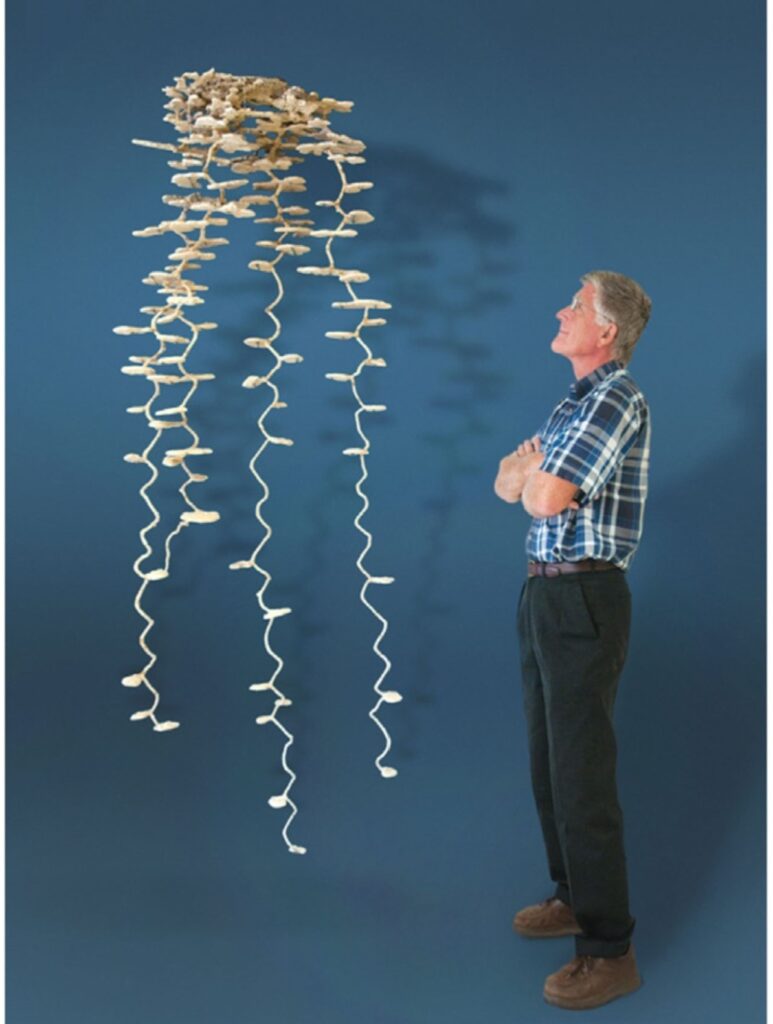

Derinkuyu extends to more than 85m below the surface with the lower limit being set by the water table and comprises 18 levels of tunnels which include spaces for living, storage, communal eating, kitchens and food processing.

There are even clearly identifiable churches in the deeper sections with rock cut benches, pulpits and altars. This makes sense as these are the most recent levels and were constructed during the Christian period. This places these parts after three or four hundred AD. Furniture throughout was not required as benches, sleeping cubicles and tables are simply carved out of rock. When more room was required, they simply dug out what was needed. This accumulative process accounts for the “organic” feel of the place not unlike an ant colony as Graham points out. It explains its maze-like quality.

Cappadocia’s underground cities were clearly carefully thought out but equally clearly, not planned as a single project. This is the work of millennia and its “ad hoc” lay out demonstrates the process of continual addition and modification. These communities were dedicated to the task of building and maintaining these underground cities, creating ‘normality’ sometimes at the most challenging times! They must have been a wonderful sight with a fabulous community feeling.

Does this mean the tunnels were excavated in prehistoric times or at the end of the last Ice Age? Maybe. People have certainly lived here and travelled across this region since Neolithic times and tool technology is not restricted to a particular defined epoch or “Age.” As we pointed out in our Travel Journal about the new Van Museum https://www.easternturkeytour.org/van-museum/, stone tools were used well into the Chalcolithic Age, Bronze was used well into the Iron Age and so on.

Graham Hancock, a journalist who has spent decades researching and writing about a distant and forgotten part of human history, speculates that the tunnels were Ice Age refuges from catastrophic cosmic impact events marking the onset of the Younger Dryas. This is the period that sees the emergence of sites like Nevali Çori, Göbekli Tepe and Karahan Tepe along with many other sites in the northern arc of the Fertile Crescent that seems to be witness to a new dawn of human consciousness apparently “out of nowhere,” as Graham Hancock once said with reference to Göbekli Tepe.

Academics suggest that these tunnels were originally used for storage in the near surface levels and as parts of surface dwellings before being expanded over time as needs determined, reaching its greatest extent during the Byzantine period when Arab Muslim raiders crossed the region in the 7th, 8th and 9th centuries. At its peak during the late Byzantine period, it is believed that up to 20,000 people could have taken refuge for weeks at a time in Derinkuyu alone.

The best way one can really decide between the two interpretations is to go and see for yourself. Join us on one of our brilliant tours that will take you into the distant past where you will get the chance to absorb the air and touch the places that our ancestors knew. Seeing is believing and seeing will give you an experience of a lifetime; a valuable opportunity to explore and immerse yourself in the secret world beneath the other worldly surface of Cappadocia.

Most of the large underground cities share a common feature of large rolling doors looking like mill stones that could only be opened or closed from the inside and which effectively sealed the inhabitants off from the outside world creating a bunker like environment, secure from threats above.

Many of the bigger underground cities are connected by tunnels. Kaymaklı, for example is connected to Derinkuyu by a 9-kilometre-long tunnel, an extraordinary achievement not just in engineering terms but in the endurance needed to get from one complex to another in claustrophobic tunnels with only basic flame lamps to light the way!

Kaymaklı, although open to the public, is less frequently visited but is also extensive in size and its scope is considerable. Only four levels are accessible but while eight levels have been identified, it is not known how big the complex actually is. It has the usual suite of communal rooms, living quarters and food processing areas along with stables in the upper level and it is estimated that about 3,500 people could have been accommodated here along with some supplies and possessions.

The region’s geology and physical geography are perfectly suited to this kind of underground construction: the dry conditions and the nature of the rock, which is soft when first cut but which hardens on exposure to the air makes for easy mining in naturally well supported tunnels and cavities with a predictable and consistent water table from which to draw potable water. The rock is almost like a natural, self-hardening cement.

Article continued below…

The volcanic strata, which dominates the physical geography across Cappadocia is known as “tufa” and is easy to carve with even basic tools. This is the same pyroclastic material from the eruption of Mt Hasan that has in combination with water, ice and wind naturally produced the fairy-tale chimneys and phallic columns jutting from the earth above ground and made the excavation of Churches, Monasteries and homes the norm for the region. These surface features are the first natural wonders that catch the visitor’s eye.

Heading south from the main area of tufa dominated landscape into the Konya Plain, the Ihlara Valley, cut into the landscape by the Melendiz river, is an amazing year-round lush oasis with its own microclimate.

Studded in the canyon walls and cliffs are dozens of small churches and hermit refuges but at the head of the Valley is the jaw dropping Selime Monastery.

This is a significant rock-cut construction and the largest religious structure in the whole Cappadocia region with a cathedral-sized church cut directly into the volcanic tufa complete with towering decorative columns cut from the living rock along with adjoining chapels and galleries.

The monastery complex is separated into multiple sections with kitchens, stables and living quarters, some of which are still adorned with now weathered frescoes, stretching up the cliff and into the mountain.

Signs of early civilizations are also present in and around the Ihlara Valley: prehistoric hunter gatherers, early farmers, Hittites, Phrygians, Persians, Romans, Early Christians, Byzantines, Seljuk Turks and Ottomans are some of the many occupants of this valley and the wider area.

The extensive Selime Monastery Complex is thought to date back to the 8th or 9th century BC but has gone through many periods of adaptation and changed use with its most extensive expansion coming during the Christian period and its use as a monastic centre.

The upper section superficially resembles a fortress with well-preserved walls, gullies and trenches as well as steep rock staircases and hidden passageways. As an important section of the Silk Road, the complex was converted to a Caravanserai sometime in the 12th or 13th centuries during the Seljuk period.

Caravansaries were key parts of the Silk Road network and provided refuge for travellers and merchants who journeyed along the route’s many branches and tributaries and were important factors in promoting trade and stability.

You will have passed by several Seljuk Caravanserais on the road down to the Ihlara Valley and on the road further along on the way to Konya is a stunning example of the traditional Caravanserai building, Sultanhanı, at Aksaray.

The network of Caravanserais was introduced as a formal system by the Seljuk Turks when they arrived in Anatolia in the 12th century. A toll was charged to use the road but accommodation for up to three days at a time along with food, fodder and medical care was free.

A specific monument to the arrival and presence of the Seljuks is the Tomb – or “Turbe” – of Selime Sultan which displays an architectural style from the 13th century AD and is a rare example of its kind in the Anatolia region. However, the Seljuks made a huge imprint on Central Anatolia with the major Seljuk administrative and religious centre just south of here, the city of Konya, their capital city at the time.

Article continued below…

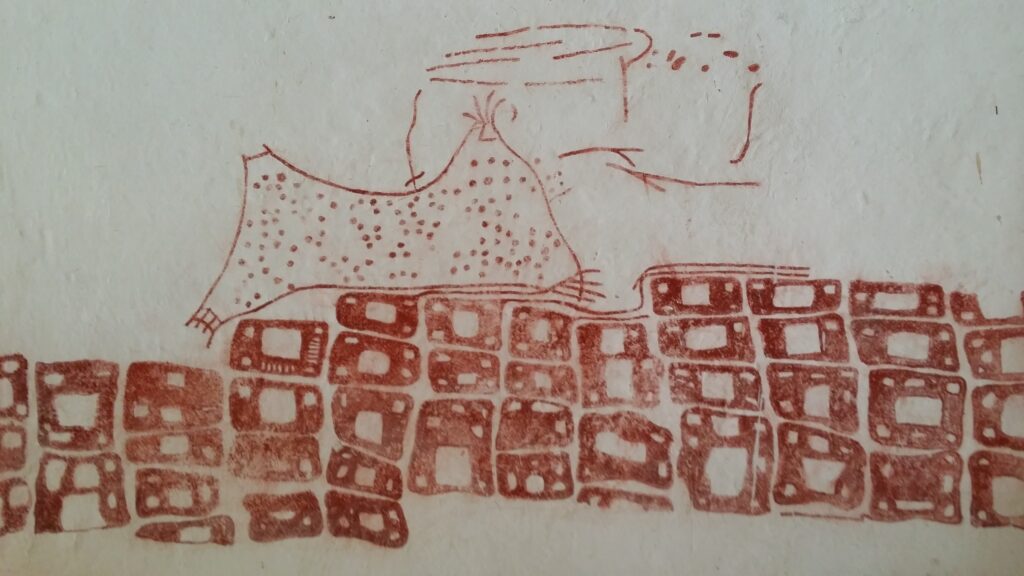

This entire region has been inhabited since Neolithic times and some of the earliest urban developments are found here including Catalhoyuk on the Konya Plain, a settlement going back to about 7,500 BC, and which even contains a wall painting depicting the eruption of Mt. Hasan, the volcano ultimately responsible for creating the extraordinary landscape of Cappadocia and contributing to its agricultural fertility.

Right across Cappadocia one is struck by not just the monumental scale of the natural landscape and the structures that spring up or descend into the ground all around you, but also the human touches and the intimacy of some of the nooks and crannies one stumbles upon. There is the constant question: “Who would have lived in a house like this?” It’s all so familiar, but yet so different.

The whole area and so much of what is in it invites speculation, but it is worth remembering that it tells you what it tells you, nothing more and nothing less. This is beautifully captured in the advice of the great Muslim Sufi mystic, Mevlana, who lived and taught in Konya:

“Söyledikleriniz karşınızdakinin anlayabileceği kadardır.” or in English “That which you say is what the person in front of you will understand.” In other words, it’s about the content.

Sometimes if you want to shed a little light onto things you have to go groping about in the dark. When it comes to these incredible underground cities, we are still in the dark about most of it. However, our imagination and sense of adventure brings us back year after year. What better way to gain a greater insight into our ancestors and their long-forgotten history.

Keep up with our travel journal updates as new underground cities are being discovered all the time. This wider region is full of possibilities. A new and significant underground city is being opened up in southeast Turkey at Midyat, and it will soon be on our agenda.

We’d love it if you, your friends and family could join us on this epic journey (above and below the earth’s crust). Thanks for reading our latest travel journal (please share), there will be more to come so keep posted by following our social media pages:

www.facebook.com/EasternTurkeyTours

Instagram account @eastern_turkey_tours

Happy travelling – Sally and Nick.